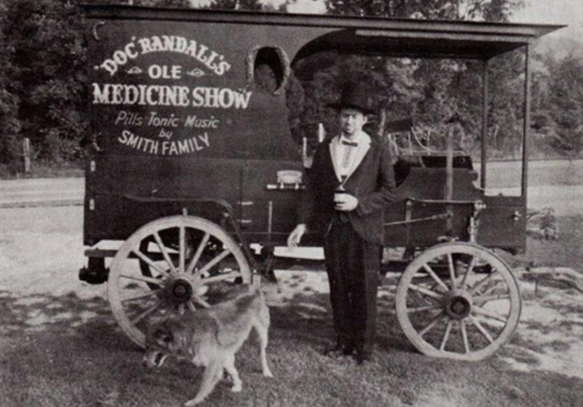

Photo courtesy of EDRM (edrm.net)

History has a way of repeating itself.

At the very end of the 19th century, “patent medicines” were all the rage. Tonics and elixirs were available to cure every kind of ailment. Some of them were bought by people who didn’t even have any ailments. A few worked; most didn’t; and a few had fatal outcomes.

130 years later, AI platforms and generative AI applications are being sold to address every kind of corporate ailment. And even if there’s no specific need, many companies are buying these tools and then trying to find uses for them. Some work well; most yield disappointing results; and there have been some fatalities.

Among the best known of these early ‘cure-alls’ was snake oil – which has since given its name to any kind of product that sounds too good to be true. And those who sold it have also been immortalized as snake oil salesmen – a term which we still associate with someone who has a very compelling pitch for a product that we know we really should be suspicious of.

Interestingly enough, snake oil does indeed have curative powers related to muscle and joint pain. It was introduced to this country in the 19th century by Chinese immigrants who came to work on the transcontinental railroad and brought their traditional medicines with them. The issue was that their salve was made from Chinese water snakes – and the Chinese water snake population in the United States was exactly zero.

Not wanting to let a detail like that get in the way, industrious – and shady – entrepreneurs of the period took to boiling any kind of snake they could find. And they frequently supplemented their concoctions with castor oil, mineral oil, hot pepper, and even paint thinner. They leveraged the public’s desire for better health, and the hype around the latest cure-all. People bought the product; most were disappointed with the results.

Starting to sound familiar?

By 1906 the roots of what we now know as the Food and Drug Administration were formed. Within a few years, fake medical claims that were meant to trick buyers were outlawed as unfair practices. Soon after, additional laws regarding the safety and purity of drug ingredients were passed. Around the same time, the Federal Trade Commission was empowered to oversee the advertising of all FDA-regulated products.

So what does this have to do with AI?

Last December the FTC announced an enforcement action against a major national pharmacy chain – ironically, not for anything related to pharmaceuticals, but for unfair practices related to its use of AI-powered facial recognition technology as part of a theft deterrent system. It’s a major development in the rapidly evolving AI regulatory space because it’s the first time that the FTC has pursued a company for using AI technology in a way that is alleged to be biased and unfair. It also highlights the FTC’s continued use of a settlement order that requires companies to completely delete all the data that was acquired via the cited platform, as well as destroying any models and algorithms which were used to process that data, and obtaining similar evidence of destruction from any third parties who may also have had access to the data.

As a for-profit enterprise, it’s likely that this retailer didn’t set out with the purpose of harming or harassing its customers. Like most companies, it had a desire for greater financial health (by reducing losses due to theft) and bought into the hype around the latest corporate cure-all (in this case, AI-driven facial recognition technology). Said another way, the company appears to have its hands on a bottle of digital snake oil.

130 years ago, the problem wasn’t with snake oil per se: it was an issue of its efficacy being oversold to people who really wanted it to work. They were lured in by claims that, in retrospect, seem pretty outrageous – but at the time they suspended their skepticism in hopes of finding some kind of relief.

The recent action by the FTC contends that the pharmacy chain didn’t reasonably assess the accuracy of its tech solution before moving it into production; that they didn’t enforce data (image) quality controls, which increased the odds of false-positive alerts; and that they also didn’t monitor their AI model for bias – which was indeed present, and which caused certain groups of consumers to have a higher likelihood of being falsely identified by the application. All because they really wanted to find a solution that worked.

The issues we’re facing today – and in the very near future – aren’t with AI technology per se. But that technology is being oversold to companies that really want it to work. The risks associated with even ‘simple’ applications are not yet well understood by most practitioners – and even when they are, there’s a belief that the technology will somehow check itself and stay away from all the potential landmines (after, isn’t that why they call it ‘machine learning’ ?)

The FTC – and many other federal and state regulators, licensing bodies, professional organizations, and probably some agencies that haven’t even been created – will be charged with keeping AI applications compliant with laws that have not even been written yet. But in the meantime, keep the following in mind as you swallow a few doses of the AI miracle cure.

Successful implementations start with a clearly specified business opportunity or problem that needs to be addressed, which is then enabled with the appropriate AI/ML technology, and that technology must be driven by high-quality, high-signal data.

Regardless of attempts to personify them, AI tools are just mathematical models. Like any model, they need to be initially calibrated against a set of relevant, validated data – and then periodically re-calibrated to guard against data drift and to detect bias and unintended outcomes. Refrain from using the term ‘hallucinations’: instead, refer to incorrect output as ‘errors’ – and you’ll see how quickly the perception of AI as a kind of technological magic disappears.

When snake oil was eventually exposed as a powerful combination of hope and hype, the ‘real’ patent medicines category quickly grew larger, more effective, more profitable – and stood up to rigorous regulation. Armed with that knowledge, maybe we can step over the hope and hype phase, and more quickly get to well-planned, well-executed, safe and effective AI solutions.

To discover how our DataInFormationsm suite of solutions helps you achieve superior performance from your advanced technology investment contact Joe Bartolotta, CRO at

joseph.bartolotta@liberty-source.com